“Yes. But could I endure such a life for long?” the lady went on fervently, almost frantically. “That’s the chief question — that’s my most agonizing question. I shut my eyes and ask myself, “Would you persevere long on that path? And if the patient whose wounds you are washing did not meet you with gratitude, but worried you with his whims, without valuing or remarking your charitable services, began abusing you and rudely commanding you, and complaining to the superior authorities of you (which often happens when people are in great suffering) — what then?”

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

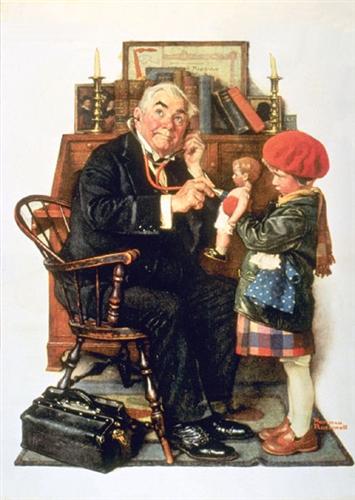

I have a collection of idyllic memories from my childhood summers, traveling with family to the sleepy New England town of Lenox, Massachussetts. There we would go hiking, watch movies, attend concerts by the Boston Symphony Orchestra at their summer retreat in Tanglewood, and swim. And we never failed to visit the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge. Rockwell was one of the most well-known American painters of the twentieth century and some of his famous works appeared on the covers of the Saturday Evening Post. His humorous, sentimental, and occasionally somber paintings capture everyday American life during the early and mid-twentieth century, portraying families eating dinner, children arguing about a basketball game, and teenagers at a lunch counter.

|

|

| Norman Rockwell, Doctor and Doll (1929) Curtis Publishing |

One painting in particular sticks out in my mind, Doctor and Doll, drawn for the Saturday Evening Post cover of March 9, 1929. A dapper physician in a suit and tie sits in a chair. A young girl in her winter clothes with a hat, scarf, and mittens scowls at the doctor, reluctant to let him examine her. She’s upset, as so often children are, to be seeing a physician. She holds her doll up to him as he gently pretends to listen to the doll’s heart with his stethoscope. He plays along with the young girl, earning her trust so that he can, perhaps, listen to her own heart next. The doctor does not look down at a note or a chart while taking care of his patient. He’s not rushing to leave. He merely attempts to establish trust and takes the time necessary to earn it. It is the paradigmatic image of what we want a doctor’s interaction with a young patient to look like, an idealistic portrayal. And Rockwell realized that this was true of many of his paintings. He once said: “The view of life I communicate in my pictures excludes the sordid and ugly. I paint life as I would like it to be.”

But hyperbole, though an artistic strategy, is not always evident to children on family vacations. While the Rockwell painting does not exactly illustrate my expectations of medicine, it does exemplify a certain naïveté with which I approached medical school. I knew I would work incredibly hard and I also knew, after reading firsthand accounts from several physicians, that I would see horrible things. However, I retained some of that boyish optimism about medicine and imagined that the majority of my interactions with patients would be as depicted in Rockwell’s painting.

Since then, however, much has changed. I was recently chased down the hall by a psychiatric patient who had a low sodium level (which can lead to seizures). We needed to get a sample of his blood to recheck his electrolytes, but he refused and when I tried to explain to him why we needed to get labs, he jumped out of bed and ran after me, saying: “I’m going to f***ing show you how I do things.” Another patient recently told me “I don’t need to f***ing be here” and ran out as I chased after him. I have been called an “idiot” and a “fraud.” I have also been screamed at, given the middle finger, and physically threatened. Yet another patient threatened to report me to the New York Times because his room was too hot. I have tried convincing countless numbers of patients (sometimes successfully and sometimes not) to take life-saving medications. I saw a patient fall out of her bed, micturate on the floor, and go into cardiac arrest. Another patient threatened to slap me after I ordered an EKG to examine his arrhythmia more closely. There have been times when I have had to choose between spending time writing notes and speaking with patients and their families — and have paid the price for choosing the former. I have performed CPR more times than I’d like to think about. And there is, I am certain, more to come.

None of this is evidence that I have come to dislike practicing medicine. I selectively edited out the brighter episodes to make a point: medicine is a universe away from what most of us perceive it to be. It is far more dark, depressing, and quick-paced than anything I imagined. It is, in short, messy. But I believe it has always been this way. Samuel Shem’s The House of God, published in 1978, is a satirical novel filled with familiar yet horrific stories and bizarre interactions that characterize a physician’s first year of residency. (I’ll write about this book in another post.) That experience of some forty years ago is hauntingly similar to my own. The passage at the beginning of this post from The Brothers Karamazov, completed in 1880, resonates with me as well.

Residency has altered my expectations. Humans have always been sick and will probably always face sickness and death. And sickness and death are deeply unsettling experiences that sometimes prompt strange and disturbing behaviors. They challenge our youthful notions of invincibility and immortality. They expose our weakness and decrepitude and force us to confront an end that none of us can face with a straight spine. A hospital lays bare these notions — and the whole experience makes it difficult to be calm, reasonable, and understanding. Who can be levelheaded in this perpetual twilight?

For that we must return to Rockwell’s comforting painting, a glorified image of what we want from medicine. If we look closer we may see the painting differently. The doctor has made little progress with his patient. The girl has not removed her hat, scarf, or shoes. She has not yielded one bit. She merely lets her doll be the “patient.” And yet the doctor readies himself to do whatever it takes to help her. Almost imperceptibly smirking, he patiently listens to the doll’s chest. He is not angry or frustrated but sympathetic. Perhaps we can face the daily frustrations of the hospital better with some of that Rockwellian spirit to strive for life as we would like it to be.

"And yet the doctor readies himself to do whatever it takes to help her." Love this line. For all of us, whatever our chosen craft, this is an important question – are we truly ready to do whatever it takes to help our customers? Even if they are screaming at us and threatening to sue (and whatever other ridiculousness you've had to overcome)? Thanks as always for sharing your wisdom and perspective!!

An older physician reminded me that I have the great privilege of seeing a person at their worst. It is impossible to experience their subjective reality of chronic pain or acute illness. A man with a full stomach remembers hunger but does not feel hunger. And yet I have a schedule to keep… the work…. to balance my humanity and the requirements of a job.

nice