By early 1967, just months after Ronald Reagan’s election as governor, James Q. Wilson had already tired of East-Coasters’ new favorite pastime, “Explaining California.” So the California-born Harvard professor penned a firsthand account of growing up in Long Beach, “to try to explain what it was like at least in general terms, and how what it was like is relevant to what is happening there today.” As Wilson explained in “A Guide to Reagan Country,” Reaganism reflected a southern Californian individualism focused not on changing the world but on improving your own small part of it — your home, your yard, and, before you were old enough for any of that, your car.

“Driving. Driving everywhere, over great distances, with scarcely any thought to the enormous mileages they were logging. A car was the absolutely essential piece of social overhead capital,” he recalled. You needed the car to “get a job, meet a girl, hang around with the boys,” go to the movies, to the beach, to Hollywood.

In the decades after writing that essay for Commentary, Wilson became the nation’s most insightful political scientist. From his early essays on city politics, to his studies of bureaucracy and police behavior, to his writings on morality and character in American life, Wilson saw more keenly than anyone else the relationships between American character and American institutions. And throughout his career, he returned time and again to cars — in California, in America, and in the crosshairs of progressive technocrats.*

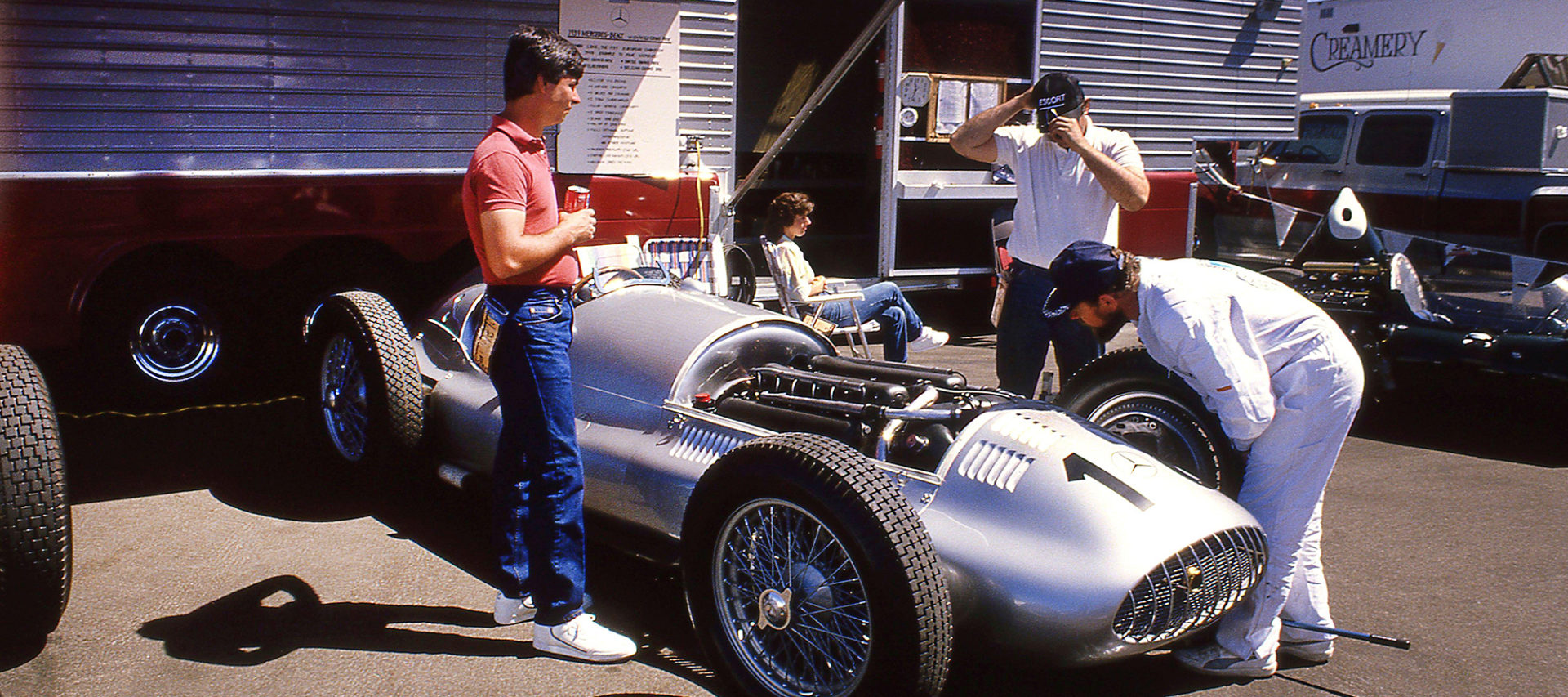

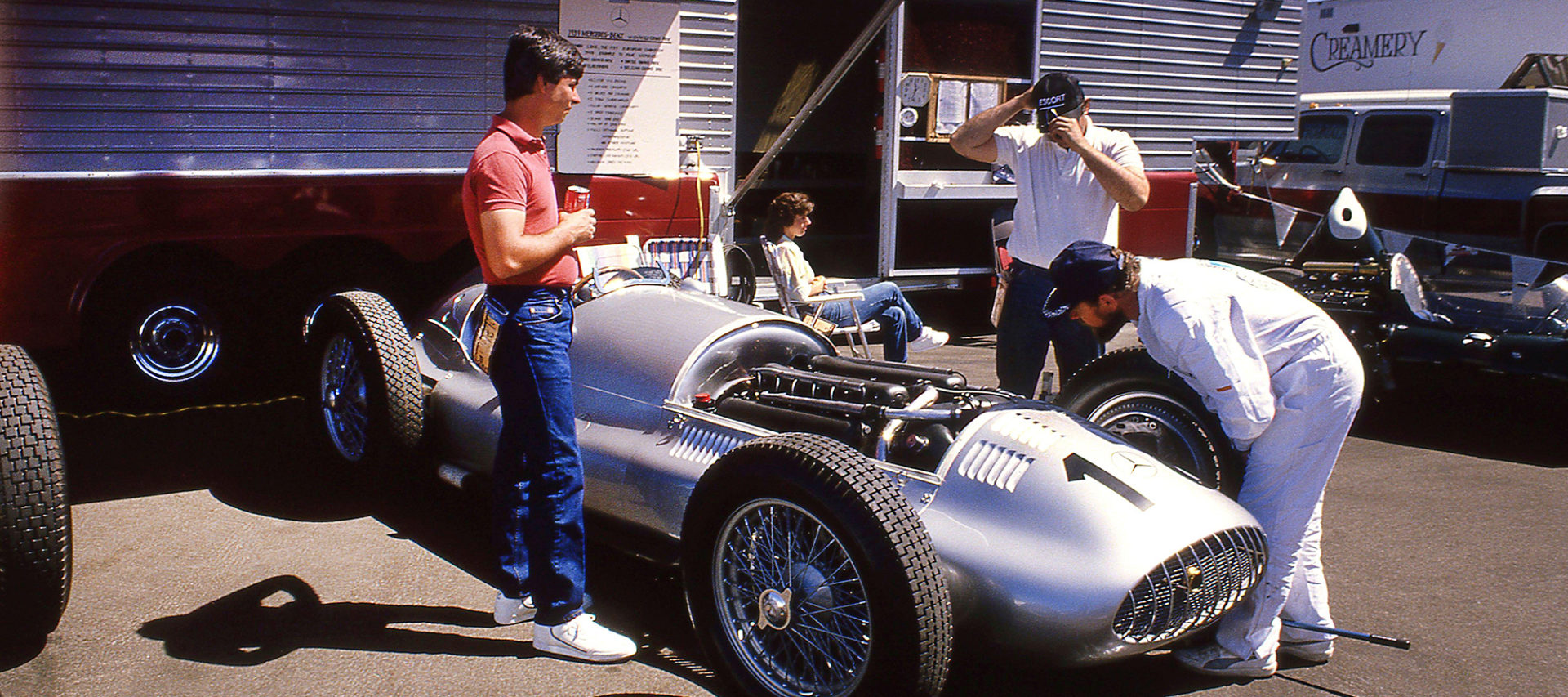

His consideration of cars was more than academic. The son of an auto-parts dealer, Wilson loved to drive “very fast,” Christopher DeMuth remembered, “preferably with his wife Roberta at his side to share the thrill.” In Cambridge he shunned the standard-issue Harvard-prof Volvo — as a 1970s protester’s sign once complained, “James Q. Wilson Drives a Porsche.”

But for Wilson, owning a car meant not only enjoying the thrill of driving it, but also shouldering the responsibility for maintaining it, repairing it, improving it. Wilson knew this in his own life — his friend Shep Melnick recalled to me that Wilson once missed a Harvard meeting because his Porsche broke down en route, and he insisted on fixing it himself — but he also saw that it was central to the car’s importance in American life generally. The importance of a car was in gaining true ownership of it, and in the process gaining true ownership of one’s self.

Of course, a young man growing up in southern California wanted a car because of the pleasures it could deliver. “But the hedonistic purposes to which the car might be put did not detract from its power to create and sustain a very conventional and bourgeois sense of property and responsibility, for in the last analysis the car was not a means to an end but an end in itself.” If New York or Philadelphia neighborhoods raised boys with a sense of “territory,” Californians raised them with “a feeling of property.” And that feeling of ownership was nourished in the driveway, or the garage, or the alley, coaxing the power and beauty out of old Fords.

Today the young American who wants to tinker with his car faces an entirely different set of challenges. Matthew B. Crawford, a political philosopher and motorcycle mechanic (and a fellow contributing editor to this journal), writes in his 2009 book Shop Class as Soulcraft, “Lift the hood on some cars now and the engine appears a bit like the shimmering, featureless obelisk that so enthralled the proto-humans in the opening scene of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. Essentially, there is another hood under the hood.” We’ve traded genuine ownership and mastery for a combination of aesthetics and access to expert help.

Crawford’s first book (and the 2006 New Atlantis essay upon which it was based) was an appeal for more of us to get underneath modern life’s hoods: to study, to struggle with, and to master the machinery under our world’s slick outer shells. From cars and motorcycles, to appliances, to the rest of our day’s infrastructure and technology, Crawford urged us to roll up our sleeves. For only by moving from superficial abstractions to the brutal reality of working imperfect materials with imperfect tools can we appreciate what is necessary for “self-government” in both senses of the term.

Crawford returns to these themes once more in his new book Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road. Those who enjoyed Shop Class will no doubt enjoy his latest volley, which once again benefits from Crawford’s autobiographical and biographical sketches, not to mention his hand-drawn sketches of the crankshafts and other gear that he’s writing about. And those who enjoyed his second book, The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction (2015), will appreciate his argument that self-driving cars will bring not more freedom but more captivity.

But in moving from the garage to the highway (and the desert, and the demolition derby), Crawford does more than simply illustrate the further joys that await your inner Steve McQueen. This new book makes even clearer the fact that our choice between driving and being driven, between making and being made, is ultimately a choice between republican self-government and administrative rule.

The way we drive our cars increasingly resembles the way we maintain them — which is to say, we do less and less of it. “With no shifter and no clutch, you don’t really feel that you are doing anything,” Crawford observes. “This lack of involvement is exacerbated by features that partially automate the driving task, such as cruise control.” Navigation is largely automated too, thanks to GPS. “Between the quiet smoothness, the passivity, and the sense of being cared for by some surrounding entity you can’t quite identify, driving a modern car is a bit like returning to the womb.”

Except for the electronic alerts, which we hear more and more. First limited to reminding you to buckle up, or to turn off that turn signal, now our cars beep to tell us that we’re drifting into the next lane, or that someone’s in our blind spot, or that there’s an object near our fender. These are intended to help, and they do — at least in the short run.

In the longer run, however, these nudges make us worse drivers. Crawford quotes a 2016 study published by the Association for Computing Machinery, which warns that “one unintended consequence of alerts and alarm systems is [that] some drivers may substitute the secondary task of listening for alerts and alarms for the primary task of paying attention.” We become complacent, ill-equipped to actually handle problems when they arise, and “the automation’s underlying assumption of our incompetence becomes progressively self-fulfilling.”

We drive ever more powerful cars, yet we assert ever less power over them.

Crawford experiences this loss of control firsthand, when he’s suddenly presented with the opportunity to test-drive an Audi RS3. Fearing that his future enjoyment of his own Volkswagen might be spoiled by driving this modern machine — “400 horsepower from a turbocharged, five-cylinder engine mated to a seven-speed, dual-clutch automatic transmission with paddle shifters…. 0 to 62 mph in 3.7 seconds in real-world tests” — Crawford expects excitement, yet experiences something more like Novocain:

There were a few on-ramps in the course of the drive, and traffic was light enough for some spirited maneuvers. But I could not connect with the car. I had it in the most aggressive of its driving modes (these determine the throttle map, shift responses, and suspension settings), but it still felt like there was a layer of decision-making happening somewhere else. The paddle shifters felt like what they in fact are: mere logic gates. I’m sure living with the car for an extended period would have allowed me to develop more feel for it, more connection, but my first impression was that it seemed to have its own priorities. It took my shift commands as a general statement of mood, a request to be given due consideration when the committee next convenes.

By contrast, driving a “driver’s car” accomplishes the opposite sensation: a “disappearing act” in which the car becomes a seamless extension of one’s own limbs, mind, and will, “a transparent two-way conduit of information and intention” that transmits tactile feedback to the driver who can respond immediately and directly in turn.

Crawford warned of automation’s effects in The World Beyond Your Head, and so did Nicholas Carr in The Glass Cage (2014): “an erosion of skills, a dulling of perceptions, and a slowing of reactions” that “should give us all pause.” But as political philosopher Harvey Mansfield warned in a 2006 essay on “rational control,” automation erodes more still. Our world’s “small matters of convenience” — the sinks and toilets that run automatically, the lights that turn themselves on and off — substitute rational control for human responsibility, and thus for human virtue. When the “point is to save you the inconvenience of having to be mindful,” then “all are treated as if they were absent-minded on the chance — of course, the good chance — that some of us might be.”

The result is that eventually more of us, or all of us, really will be absent of mind. When we submit to a form of rational control that “locates all reason in the controller, none in the nature and fortune that he controls,” we are left “with nothing to do and no virtue to practice.” In Machiavelli’s Mandragola, Mansfield observes, “all the characters get what they really want, both material satisfaction and public respectability. What they do not receive is any satisfaction proceeding from the activity of virtue.” At its worst, a regime of rational control corrodes the self-esteem that nourishes peoples’ love of liberty, and public officials’ “public spiritedness and laudable ambition.”

This is the crucial message of Crawford’s book. “Virtue is more like a skill,” he writes, “acquired through long practice in the art of living.” And that practice depends upon the choices we make, and the choices we make about which choices we make. When we choose to delegate choice to rational control outside our immediate involvement, we choose wittingly or unwittingly to shape ourselves accordingly. We “become a certain kind of person,” Crawford emphasizes. “As embodied practical skills, the virtues have to be exercised or they atrophy.” And so when we drive autonomous vehicles, or cede control to other forms of automatic convenience, “it is we who are being automated, in the sense that we are vacated of that existential involvement that distinguishes human action from mere dumb events.”

True, Crawford concedes, our increasingly automated cars often leave nominal space for human discretion and initiative, in that we can take steps to override rational control. But “it takes a certain amount of assertiveness to override automated systems, as the presumption is always in their favor.” And such assertion “is possible only if one has confidence — not only in one’s skills, but in one’s understanding of what is going on, and how to fix it. With such confidence, one does not develop a habit of deference, but the opposite.”

Crawford’s protagonists do not lack confidence, to say the least. In Why We Drive, his arguments are not merely theoretical, or only autobiographical. Crawford serves also as an immersed anthropologist of sorts, reporting from races and gatherings around the country.

He introduces the reader to drift racers at the Virginia International Raceway near the North Carolina state line, who in thousand-horsepower cars turn corners nearly backwards, “which has the visually elegant effect of prerotating the car, pointing it in the direction it will be headed as it exits a 180-degree turn.” In the Shenandoah Valley, we meet contestants at the Warren County Fair demolition derby, where “the winning strategy is to use the back of your car to ram the front of others’ cars.” (Once upon a time, I loved the Dubuque County Fair’s version of this.) Out west, Crawford profiles Journee Richardson, one of many competitors in the Southern Nevada Off Road Enthusiasts’ (SNORE) 250-mile desert race: “Nobody in the 1980s would have thought it possible that a six-thousand-pound vehicle could go over a hundred miles per hour through big bumps in the desert, but that’s what forty inches of suspension travel and massive, externally cooled shock absorbers have accomplished.”

This is all great fun, of course, but it is more than that. In these people, and in their communities, Crawford sees Tocqueville on wheels.

The Nevada event is “democracy in the desert,” for at the drivers’ pre-race meeting, organizers lay down the ground rules, from the federal and state wildlife issues to “the peculiarities of the course, in which there was limited room to pass in many areas, and curves where you really do need to go slow.” Each driver wants to win, no doubt, but all the drivers understand that they must protect themselves and each other. They must even protect the race itself — and thus the community through which the race passes, obeying a speed limit that was “strict” yet enforced solely by the honor system. “At stake was a long tradition of good relations between SNORE and the people of Caliente.” The voluntary community of racers came together, like civic groups and frontier towns, to take responsibility for themselves.

It turns out that desert races, like democracy, are more than just a matter of ambition counteracting ambition. The system presumes a certain measure of self-restraint and virtue, too.

If democratic character is found in the desert, then perhaps that simply reflects the fact that it has been cast into exile by our administered age — we live automatically and are governed bureaucratically. And the automation facilitates the bureaucracy, for as Crawford warns, “automaticity becomes a political mood, no less than an engineering project.”

Hence Crawford’s jeremiad against driverless cars. If Silicon Valley, Detroit, and Washington succeed in delivering a future in which driverless cars predominate, then America will lose one of its most important realms of personal responsibility and competence. As we trade driving for being driven, we will lose our capacity, even our appetite, for self-government.

In Why We Drive, Crawford has more specific and immediate complaints, too. Even in a world of big data and machine learning, driverless cars will not be able to accumulate and rationalize all the subtle forms of information and value judgment embodied in the norms and rules of driving. Nor will they be able to replicate the judgment and prudence that the task of driving calls for. Friedrich Hayek might warn enthusiasts of driverless cars about “fatal conceit.”

Then again, some of them readily concede the point. For example, futurist Peter Schwartz recently made that point in a talk on “The Future of Mobility.” While extolling the benefits of self-driving cars, he cautioned his audience to recognize their limits:

Imagine, for example, a self-driving vehicle trying to get through the center of Amsterdam, through the little streets with canals, right — with bicycles everywhere, little turn-outs everywhere, cars stopped and delivery vehicles….

How do you handle all that? Well you can’t, yet, with automated vehicles. So it is very, very likely that, despite the improved capabilities, self-driving automated vehicles will happen in some places fast, and other places very slow.

The places where it’ll happen fast is where you can control behavior very significantly and where you have a very modern infrastructure. So the most likely place in the world is Singapore. So Singapore is probably going to be the first place that actually abandons private vehicles and moves toward self-driving vehicles. And they already have a plan.

Driverless cars will initially be harder to deploy in Amsterdam or London, Schwartz concludes, but “it won’t be so hard in Los Angeles.” So their best initial uses might simply be to ease the chore of a long daily commute from the suburbs to the city, at which point the drivers themselves will have to handle the last couple of miles.

But what will drivers do when they aren’t driving? Crawford notes that driverless cars are marketed toward our desire to free up more time for either work or leisure — the Volvo Concept 26 is marketed with a photo of “a man who is obviously a creative,” with “flowing, Lord Byron–like hair” and holding “what appears to be a small leather-bound volume of poetry in his lap.” Yet the more likely outcome is that the commute will become yet another moment of captive attention to be filled with advertisements. Our own cars will become smaller versions of the airport terminals Crawford described in The World Beyond Your Head: an “attentional commons” filled up with screens and speakers. If so, then someday the luxury cars will be the equivalent of airlines’ premium lounges, where we pay extra for a little peace and quiet, or the equivalent of streaming services for which you pay a premium if you want the ad-free version.

And while driverless cars are today presented to us as a new and exciting choice, that choice is only temporary. At a 2015 conference, Elon Musk predicted that once driverless cars become predominant, lawmakers “may outlaw driven cars because they’re too dangerous.” On that point, Crawford agrees: Driverless cars’ “inherent logic presses toward their becoming mandatory — if not by fiat of the state, then by the prohibitive calculations of insurance companies, who will have to distribute risk among fewer human drivers. Or by the portioning out of scarce road surface, with preference given to driverless cars.”

As it happens, the Singapore plan, Peter Schwartz explained in his talk, was to eliminate older cars by fiat, as well as private cars generally. “Within twenty years there will be no more private cars in Singapore; they will all be self-driving electric vehicles…. Singapore will be the first place on the planet that abandons the private vehicle and moves toward self-driving, automated mobility services.” With apologies to Francis Fukuyama, this all begins to feel like the “end of history.”

On the last page of his famous 1992 book on that subject, Fukuyama noted that “Alexandre Kojève believed that ultimately history itself would vindicate its own rationality. That is, enough wagons would pull into town such that any reasonable person looking at the situation would be forced to agree that there had been only one journey and one destination.” (Perhaps the wagons will have driven themselves there.)

But the comparison between Crawford’s argument and Fukuyama’s is more apt than that. For as Fukuyama explained, the end of history could reflect the successful channeling of humankind’s sometimes combustible energies toward safer ends: “In the future, we risk becoming secure and self-absorbed last men, devoid of thymotic striving for higher goals in our pursuit of private comforts.” Or, as he put it in the original essay on which the book was based,

The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.

In hindsight, this sounds like an advertisement for Tesla Autopilot.

Sad or not, the future will be justified in terms of safety. Safety surely is a good thing, and unsafe drivers surely are not. But you can have too much of a good thing, and we do. Our tools already have been trial-lawyered to a point of absurdity, and that is just the start of it. (Crawford’s brief digression, on the absurdly counterproductive design of the newest “safe” gas-can nozzles, is the truest thing I have read all year.) In our society, he observes, “those who invoke safety enjoy a nearly nonrebuttable presumption of public-spiritedness.” It is hard to argue with safety, especially when projections of human lives lost on the road are much easier to quantify than the loss of human spiritedness that we will accept instead.

The future of driverless cars is a future of mass transit. Today’s car is a private, personal alternative to the bus or train. Tomorrow’s car is the bus or train, just with fewer seats. It will at least bring you to destinations beyond the bus route or train line, but in every other way it will be mass transit, leaving us passive as we are carried to our destination of choice. (Unless, that is, driverless cars ultimately limit those choices too.)

Of course, for those who prefer mass transit for themselves or for the masses that they administer, passivity is a feature, not a bug. And to be sure, the driverless future’s apparent imminence reflects in no small part the attraction of this new technology’s benefits. Many, many drivers like the car of the future more than the car of today, and for palpable reasons. Driverless cars may well free up time and money for other pursuits. Indeed, driverless cars’ disruption of twentieth-century transportation echoes the original automobiles’ disruption of nineteenth-century transportation — to say nothing of the myriad other commercial technological innovations that have disrupted everything else in our lives, generally for the better.

But this narrowness of the cost-benefit analyses surrounding driverless cars is what makes the sheer breadth of Crawford’s book so important. His jeremiad reminds us that this particular technological disruption may be of a different order of social magnitude than, say, the disruption of the music industry or the camera industry or the restaurant industry. In buying, owning, fixing, and driving a car, there is much more at stake. Buying a car is a formative experience of the rewards and responsibilities of owning private property. Repairing or at least maintaining a car teaches the humility and creativity that necessarily accompanies any attempt to diagnose and solve practical problems in an imperfect world. Driving a car forces us to learn not just the written rules of the road but also the unwritten ones, as well as the prudential judgments necessary to co-exist with all the other drivers heading to their own destinations.

As James Q. Wilson saw in the California of his youth, all this is not a bad way to form a citizen capable of republican self-government.

Speaking of California, there is no small irony that the future that Crawford laments is being produced mainly by Silicon Valley. For Silicon Valley was itself produced by the character that automation now threatens. At least that was the view of Robert Noyce, one of Silicon Valley’s founding fathers, as recounted forty years ago by Tom Wolfe:

Just why was it that small-town boys from the Middle West dominated the engineering frontiers? Noyce concluded it was because in a small town you became a technician, a tinker, an engineer, and an inventor, by necessity.

“In a small town,” Noyce liked to say, “when something breaks down, you don’t wait around for a new part, because it’s not coming. You make it yourself.”

Or at least you did then. Today we surely would order the part for next-day delivery. Or we’d throw out the entire thing and order a new one. Or instead of owning it in the first place we’d simply buy access to it as a service.

Which is to say that Silicon Valley is not making an America that will make the sort of Americans who made Silicon Valley. Marc Andreesen, one of Silicon Valley’s keenest thinkers, rightly announced this spring that “It’s Time to Build.” But we need to build builders, too. Instead we are building up what Crawford calls a “habit of deference.”

Two decades after James Q. Wilson’s Commentary essay on cars, he wrote perhaps his most famous work, Bureaucracy (1989). After three hundred pages’ analysis of various aspects of bureaucracies, Wilson turned to the question of why nations differ in their tendency toward or against bureaucratic control. His analysis began by looking at each citizenry’s degree of “habitual deference.”

In Sweden, for example, Wilson traced a history of cultural deference to a modern politics in which the people “accord government officials high status, do not participate (except by voting) in many political associations, and believe that experts and specialists are best qualified to make governmental decisions.” This culture was not exclusive to Sweden, of course; “elements of it can be found in all Scandinavian nations, in Germany, and in Great Britain.” But not in America:

American political culture could hardly be described as deferential. Americans value expertise but they do not defer to it; an expert who takes an unpopular position or acts contrary to the self-interest of an individual or a group will be treated as roughly as any other adversary. Americans admire their form of government but do not admire or accord high status to the officials who work for it….

And that culture was the foundation upon which our political institutions were footed: An adversarial political culture is not unique to the United States, but it is in the United States that the political institutions — the separation of powers, judicial review, and federalism — allow it full expression and reinforce its central features. Everywhere, of course, institutions and the incentives they create interact with culture and the habits it fosters. American political culture and institutions are remarkably congruent, however, so much so that it is hard to imagine parliamentary institutions being transplanted here.

Well, maybe it was hard in Wilson’s time. In our own, however, it is much easier to imagine our constitutional institutions being supplanted by new ones — if not parliamentary, then technocratic and bureaucratic. It is easier because it has already happened, or at least is happening now.

Fukuyama has popularized the notion that all nations, in their development of political institutions, seem to be “getting to Denmark.” In driverless cars we will get there faster. The more we welcome technology’s rational control in our daily lives, the more we will welcome it — even demand it — of our political institutions. Driverless cars will take us down many roads, including the one to serfdom — unless books like Why We Drive convince us to steer to the off-ramp.

During Covid, The New Atlantis has offered an independent alternative. In this unsettled moment, we need your help to continue.