At this blog’s inception nearly five years ago, I asked myself the following question: “When you watch impressive doctors at work, what is it that most impresses you?” In other words, what makes a great physician? I was a third-year medical student at the time and I couldn’t answer the question. At the beginning of training one can hardly keep up with the incoming information, let alone consider the characteristics that make a great physician. I liked and disliked certain doctors depending on the way they treated residents, medical students, or patients. But beyond kindness, their traits varied widely. During residency I have been fortunate to work with many admirable doctors, and consequently my sample size has grown. Seeing what I’ve seen thus far, I think curiosity and humility are the two most impressive characteristics of a great physician.

|

| Wikimedia |

Galen of Pergamum (AD 129–ca. 216), the Greco-Roman doctor, wrote extensively about how to make physicians great again in his treatise That the Best Physician Is Also a Philosopher. He bemoans the lost art of medicine and the corruption of the profession. He advocates for a temperate lifestyle, arguing that if a physician puts virtue above wealth, he or she will be “extremely hardworking” and will therefore have to avoid “continually eating or drinking or indulging in sex.”

A doctor must also be “a companion of truth.” “Furthermore, he must study logical method to know how many diseases there are, by species and by genus, and how, in each case, one is to find out what kind of treatment is indicated.”

He continues,

So as to test from his own experience what he has learnt from reading, he will at all costs have to make a personal inspection of different cities: those that lie in southerly or northerly areas, or in the land of the rising or of the setting sun. He must visit cities that are located in valleys as well as those on heights, and cities that use water brought in from outside as well as those that use spring water or rainwater, or water from standing lakes or rivers.

Notice that Galen does not endorse brilliance as a required characteristic of a physician. No, he advocates for the intelligent use of one’s faculties. Indeed, he seems to favor curiosity about the surrounding world as a necessary quality for a doctor.

Curiosity, a desire to discover and a desire to know, is inseparable from a great physician. In residency we are often told by our attending physicians that we must be “lifelong learners.” Curiosity naturally creates lifelong learners. Medicine, after all, is not confined to what one learns in medical school or residency. If it were, our doctors would not be very good. One does not see every disease process in residency, one often forgets certain things, and

the evidence

and guidelines are forever changing and improving. Thus, we must always be looking up the latest evidence on the diseases we see.

Moreover, there isn’t always a clear diagnosis or treatment, and physicians must scour scientific literature for the answer. When, as so often happens, there is a diagnostic mystery, curiosity works against our inclination towards laziness and forces us to stay on our toes, question what we believe and why we believe it.

Curiosity also aids the clinician-researcher. Physicians since Galen’s time have participated in various forms of research, attempting to answer questions that have not yet been answered. For many of our predecessors the questions were quite basic, given the general ignorance about the world of biology. Yet there are still vast areas of medicine for which answers are needed. The most obvious examples in the specialty of neurology concern brain tumors or diseases like Parkinson’s. The lifespan for patients with certain brain tumors is a year and a half – how does one improve treatments for these virulent neoplasms? For Parkinson’s disease, we can only treat symptoms but cannot slow the disease down – what treatments might reverse this pathology or at least stop it in its tracks? Curiosity drives physician-researchers to make discoveries and to seek answers to these questions.

But there is another characteristic, too, necessary in order to be a great physician. The sheer volume of material one must know and understand about medicine as well as the natural world is enormous and infinite. Because of the infinite knowledge they cannot possibly possess, doctors must also confront this world with humility, humility about how much one must truly know and understand in order to be great.

What was true in Galen’s life is doubly true today: There is a vast world of knowledge in the realm of medicine. Humility, like curiosity, provides doctors with a sense of the struggle to accumulate a vast amount of knowledge. It helps them confront the possibility of being wrong. And as I’ve written on this blog, doctors are often wrong. Humility makes us more likely to double-check ourselves, to re-examine the patient when we’re unsure, to look things up when we feel insecure in our diagnosis. It makes us more thorough. It urges us to listen to the opinions of other doctors, of nurses, or even of patients.

What, then, when I watch doctors at work, most impresses me? What, then, makes a great physician? Curiosity and humility are necessary characteristics. There is not a single physician I look up to who does not have both of these qualities. These alone may not be sufficient but I have also noticed that other remarkable characteristics tend to accompany curiosity and humility: kindness, self-discipline, intellectual rigor, equanimity.

|

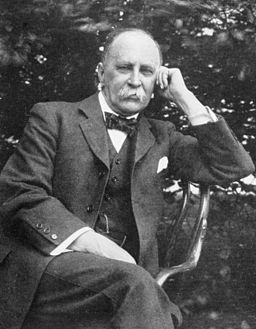

| William Osler Wikimedia |

In his valedictory address to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1889 (also known as the essay Aequanimitas) Dr. William Osler, one of the original four physicians at Johns Hopkins Hospital and a legendary professor of medicine at the Hopkins medical school and later at Oxford, discusses the quality that he thinks is most integral to being a physician – imperturbability or equanimity. He writes:

A distressing feature in the life which you are about to enter, a feature which will press hardly upon the finer spirits among you and ruffle their equanimity, is the uncertainty which pertains not alone to our science and arts but to the very hopes and fears which make us men. In seeking absolute truth we aim at the unattainable, and must be content with finding broken portions.

What lies behind Osler’s idea of equanimity is an acknowledgement of uncertainty in medicine. And such an acceptance arises first from a humble and inquisitive outlook. Curiosity and humility acknowledge this uncertainty and the need to prepare for it, with equanimity.