One of Agatha Christie’s more famous mysteries is A Murder Is Announced. A Miss Marple story published in 1950, the novel partakes fully in the anxious and pinched mood of postwar “austerity Britain.” Christie typically writes efficiently and briskly, with much give-and-take dialogue presented in short paragraphs, so the passage I’m about to cite is an unusual one: it’s essentially a monologue by Jane Marple, who is talking to a policeman who has expressed concern for her well-being — a murderer is on the loose — and would prefer her not to “snoop around.”

“But I’m afraid,” she said, “that we old women always do snoop. It would be very odd and much more noticeable if I didn’t. Questions about mutual friends in different parts of the world and whether they remember so and so, and do they remember who it was that Lady Somebody’s daughter married? All that helps, doesn’t it?”

“Helps?” said the Inspector, rather stupidly.

“Helps to find out if people are who they say they are,” said Miss Marple.

This is a story in which several characters are not — or may not be — who they say they are. So when Miss Marple continues by asking the policeman, “Because that’s what’s worrying you, isn’t it?” she puts her finger on the precise problem.

She then — and this is key — goes on to explain why the problem of identity is a particularly significant one for them, situated in their particular time and place:

“And that’s really the particular way the world has changed since the war. Take this place, Chipping Cleghorn, for instance. It’s very much like St. Mary Mead where I live. Fifteen years ago one knew who everybody was. The Bantrys in the big house — and the Hartnells and the Price Ridleys and the Weatherbys … They were people whose fathers and mothers and grandfathers and grandmothers, or whose aunts and uncles, had lived there before them. If somebody new came to live there, they brought letters of introduction, or they’d been in the same regiment or served in the same ship as someone there already. If anybody new — really new — really a stranger — came, well, they stuck out — everybody wondered about them and didn’t rest till they found out.”

And Miss Marple’s conclusion: “But it’s not like that any more. Every village and small country place is full of people who’ve just come and settled there without any ties to bring them. The big houses have been sold, and the cottages have been converted and changed. And people just come — and all you know about them is what they say of themselves.” All you know about them is what they say of themselves — this is, in a nutshell, one of the core problems of modernity.

In a sense, of course, there is nothing intrinsically, necessarily “modern” about this problem at all. Consider for example the famous case of Martin Guerre, who disappeared from his village in the Pyrenees in 1548. Eight years later a man showed up in the village claiming to be Martin and demanding his share of his now-dead father’s inheritance. Martin’s wife, Bertrande, agreed that this was her husband; he moved in; they had children together; life settled down — mostly: some in the village continued to deny that this was the man, and eventually a trial was held in Rieux to settle the question. When this did not satisfy all parties appeal was made to the court at Toulouse. In the midst of that hearing another man showed up and said that he was the long-lost Martin Guerre. After some discussion the family unanimously agreed that this newcomer was the real Martin and that the other man was an imposter after all. Eventually, Arnaud du Tilh — for that was the name of this man from a nearby village — admitted his crime and was hanged.

The story, which has been retold over and over, in books and films and plays, was a sensation even at the time: a young Michel de Montaigne attended the trial, and learned treatises about the affair were published. How could a woman not know whether a man was her husband? How could Bertrande be wrong about such a thing? Was she just lonely and overworked and happy to accept the stranger’s story, since it meant the resumption of something like a normal life for her? When she was eventually convinced by relatives to claim that the new man was an imposter, why did she agree? Had something happened to change her mind? The interest has focused on Bertrande, because she would have had the most intimate knowledge of her husband, including knowledge of his body, and the body’s testimony to personal identity was the only testimony, in that time and place, that could have added substantively to the evidence. All that anyone else knew about “Martin Guerre” was, as Miss Marple might put it, what he said of himself; Bertrande could know more than that. And yet she still affirmed, for years, that Arnaud du Tilh was Martin Guerre.

One other element of the story is significant. That Arnaud lived in a nearby village was what enabled him to gather sufficient information about Guerre to be able to impersonate him successfully: he could answer most of the questions friends and family might ask in order to confirm his identity. Yet it seems that no one ever wandered over from that village and said, “Say, aren’t you Arnaud du Tilh?” This tells us something about the insularity of those Pyrenean villages, in something close to the etymological sense of the word: they must have been little social islands.

For Miss Marple such insularity is precisely what prevents the problem of identity from arising: “If anybody new — really new — really a stranger — came, well, they stuck out — everybody wondered about them and didn’t rest till they found out.” So it was with the apparent return of Martin Guerre, a return which could only become socially problematic in a social world sufficiently small and stable that even minor differences in appearance or mannerism could become subjects of general contemplation. For Miss Marple such smallness and stability is deeply reassuring.

She associates this integral, harmonious society in which everyone knows everyone else with her youth — but then, people always do. Raymond Williams begins the bravura second chapter of his great book The Country and the City (1973) by noting that a “few years ago” — perhaps not long after Christie published A Murder Is Announced — he had read a book that made a strong claim: “A way of life that has come down to us from the days of Virgil has suddenly ended.” Suddenly! But then Williams remembered another book that had made almost the same claim — in the early 1930s: the ruin had come with, or soon after, the Great War. But (Williams discovered) people writing around the turn of the twentieth century believed that it had all fallen apart a few decades earlier. And so back we go: the “organic community of Old England” is always just out of sight, just on the other side of that hill. Williams walks the familiar line of argument all the way back to the Middle Ages. It seems almost universal for us to associate stability with our childhood, or a period preceding it, as though the world did not change until we ourselves did, perhaps in adolescence. What the great seventeenth-century mystic Thomas Traherne said of his child’s-eye view of the fields surrounding his home — “The corn was orient and immortal wheat, which never should be reaped, nor was ever sown. I thought it had stood from everlasting to everlasting” — may be a commonplace experience.

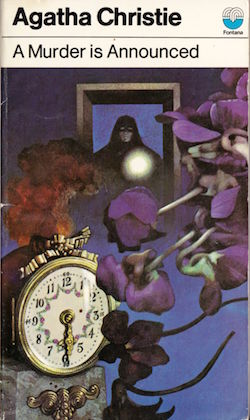

But the corn is both sown and reaped, and people change and move. The forerunners of modern identity documents appear already in medieval Europe. Occasional letters of “safe conduct” for some merchants and for individuals conducting business on behalf of the crown slowly became routine. In Britain, a statute approved by Parliament in 1414 under Henry V declared it treason to harm anyone carrying a royal safe-conduct letter and appointed officials at every seaport to ensure that the law was observed. By 1540, as the journalist Leo Benedictus notes, “the granting of travelling papers became the business of the Privy Council.” But it was not until 1795 that the Foreign Office began keeping records of passports issued, “a function that the Home Office retains today.”

Nineteenth-century passports, like the one pictured above (Kingdom of Bavaria, 1851), were used primarily for diplomatic purposes. Wikimedia Commons Significantly, British passports were generally written in French rather than English until the 1850s, a practice usually said to reflect the dominance of French as the diplomatic language of Europe and the fact that, for most of the previous three hundred years, diplomats were the people most in need of passports: it was necessary for government servants from different countries to be able to authenticate one another’s identities. There was no perceived need for documentation of identity within a country: the assumption was most people stayed where they came from, and were who they said they were. And this was a reasonable assumption: after all, the story of Martin Guerre became so famous because it was distinctive. It was the exception that proved Miss Marple’s rule about orderly, stable village society.

Nineteenth-century passports, like the one pictured above (Kingdom of Bavaria, 1851), were used primarily for diplomatic purposes. Wikimedia Commons Significantly, British passports were generally written in French rather than English until the 1850s, a practice usually said to reflect the dominance of French as the diplomatic language of Europe and the fact that, for most of the previous three hundred years, diplomats were the people most in need of passports: it was necessary for government servants from different countries to be able to authenticate one another’s identities. There was no perceived need for documentation of identity within a country: the assumption was most people stayed where they came from, and were who they said they were. And this was a reasonable assumption: after all, the story of Martin Guerre became so famous because it was distinctive. It was the exception that proved Miss Marple’s rule about orderly, stable village society.

But in the international sphere, France, in addition to providing the language of diplomacy, was among the strictest European nations in requiring foreigners to present passports before being allowed within the country’s borders — especially during the revolutionary years, and then again following the fall of Napoleon and the restoration of the monarchy. Moreover, in its anxiety to keep track of any persons who might disturb its stability, the Bourbon government mandated that all inns keep detailed records of guests, which typically meant that foreigners would need to present passports to innkeepers as well.

In a fascinating article on the development of the modern British passport, Martin Anderson notes that this French practice — and other countries’ increasingly strict passport regulations — caused considerable annoyance among many British subjects and their political leaders. Would-be travelers discovered that it was easier to get appropriate passports from the foreign embassies in London than from their own Foreign Office, in part because British passports lacked the informational detail increasingly required for travel on the Continent:

The [British] passport provided the name of the bearer but did not describe the bearer or have a space for the bearer’s signature. More than one person could be covered by a single passport. Reflecting the aristocratic notion of deference to persons with social status, servants and family members (often described only as such) were usually included on the passport of a single (generally adult male) individual. While the date the passport was issued was given, no time limit was stated. Passports did not indicate whether the bearer was a British subject.

By contrast, passports prepared at a French embassy provided suitable detail and specificity — and were done gratis, whereas the Foreign Office charged a fee, and a stiff one at that. As a consequence, by mid-century the “vast majority” of Britons abroad “traveled on foreign passports.” One Member of Parliament complained in 1850 that it was not “consistent with the dignity of England that her subjects should travel under foreign passports.”

The reluctance of the British government to reform its passport procedures despite this awkward state of affairs reflected a deep resistance among some officials to the whole practice. “The whole System of Passports,” said Lord Palmerston during one of his terms as Foreign Secretary, is “repugnant to English usages.” And the radical MP John Arthur Roebuck said he

wished to see the system abolished altogether, and that the English nation would set the example to the rest of Europe, by declaring she would grant no more passports. England should proclaim the non-necessity of them, and declare that every man who travelled did so under the safeguard of the law, and that wherever he went, as a subject of England, the power of the law protected him, so that he consequently required no passport. They were not necessary, for the rogue and the evil-designed could ever have one.

These warnings and dissents were not, however, heeded: in 1858, the modern British passport was created. Many government officials had long argued that this was necessary for full participation in modern Europe, but the desired changes were ultimately brought about in a strange way. In January 1858, an Italian nationalist named Felice Orsini attempted to assassinate the French Emperor Louis-Napoléon as he and the Empress were on their way to the opera. The three bombs Orsini threw at the carriage went off, and eight people were killed — but the Emperor and Empress remained unhurt. Orsini was arrested the next day, and it was eventually learned that he had entered France using a Foreign Office passport issued to an English barrister named Thomas Allsop — following the standard British practice of lumping several persons under a single passport. Allsop had even helped Orsini acquire the materials from which he made the bombs.

Louis-Napoléon insisted that this disaster could have been averted had the British government required proper passports, and his government demanded, with no little heat, that changes be made immediately. This contretemps provided the necessary impetus to make changes that many had been arguing for already, and the Foreign Office lowered the fee for passports and assumed full responsibility for their issuance. Crucially, another criterion was also eliminated: a longstanding rule that passports only be issued to “persons known to the Secretary of State or recommended to him by some person of known respectability.” The 1858 reform did away with this requirement: passports would now be issued to “any British subject who shall produce … a certificate of his identity, signed by any mayor, magistrate, justice of the peace, minister of religion, physician, surgeon, solicitor, or notary resident in the United Kingdom.”

The Orsini affair did not only affect British citizens traveling abroad. On the contrary, Anderson notes that, following the reforms of 1858, “the British passport was … transformed into a national document of individual identity for all Britons.” By these means, Great Britain, which was and would remain for decades the most powerful and influential nation in the world, contributed significantly to the standardization of identity documents.

The British passport was so “transformed” because it met, or seemed to meet, a need never mentioned in the debates over what the French and other European nations demanded. We may call it the Miss Marple problem: Setting aside foreigners, who always and instantly raise suspicions when they turn up in charming little villages like Chipping Cleghorn, how do you know that your neighbors are who they say they are?

In their introduction to a collection of essays extending the work of Raymond Williams, The Country and the City Revisited: England and the Politics of Culture, 1550–1850, Gerald MacLean, Donna Landry, and Joseph P. Ward note that “during the sixteenth century, most men and women worked in the agrarian sector and lived in the countryside, while fewer than five percent of them lived in towns. By the middle of the nineteenth century that had changed so dramatically that towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants together comprised roughly half the population of England.” And of course that trend has only continued, in England and elsewhere in the world, in the decades since. Such a trend means that places like Chipping Cleghorn will inevitably decline in population, affected as their people are by the gravitational pull of the great metropolises; but the resulting circulation of persons created will bring the occasional stranger into the village’s small orbit. The arrival of an Arnaud du Tilh, under his own name or some other, will be a regular, not an exceptional, occurrence. And what do the long-term residents do about that?

In A Murder Is Announced, Miss Marple comments that in the modern world, “People take you at your own valuation. They don’t wait to call until they’ve had a letter from a friend saying that the So-and-So’s are delightful people and she’s known them all their lives.” Why would anyone take an unknown woman at her “own valuation”? Surely this can only be because she dresses and speaks and acts in ways that reinforce the social standing to which she lays claim. If people look respectable, then we may with some safety assume that they are respectable. But is that sufficient? Often it is, and often it is because we assume that their identities will have been registered and confirmed by the official agencies of the state responsible for such matters.

But, thinks Inspector Craddock as he reflects on Miss Marple’s dissertation,

that … was exactly what was oppressing him. He didn’t know. There were just faces and personalities and they were backed up by ration books and identity cards — nice neat identity cards with numbers on them, without photographs or fingerprints. Anybody who took the trouble could have a suitable identity card — and partly because of that, the subtler links that had held together English social rural life had fallen apart. In a town nobody expected to know his neighbour. In the country now nobody knew his neighbour either, though possibly he still thought he did.

The Victorian MP John Arthur Roebuck’s claim that “the rogue and the evil-designed” could easily obtain passports proves to be important and troubling: if so, then all that passports (and other identity documents) can achieve is a false sense of security. In A Murder Is Announced, half a dozen characters turn out to be displaying quite false identities to the world. One of the few who isn’t altogether other than she appears is the cook Mitzi — referred to by the other characters as a “Mittel European,” which is Christie’s euphemism for “Jew” — and yet Mitzi is frequently referred to as a pathological liar. The deepest deceptions are perpetrated by the English, though; importantly, these are all aided by the dislocations of the recent war, in which several of them played a part.

But the essential point that we can discern from this brief look at A Murder Is Announced is that identity documents play a double role in the social changes that Miss Marple describes. On the one hand, they are a response to those changes: as MacLean, Landry, and Ward comment, the “profound shift [that] occurred in the balance between the urban and rural populations of England” between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries had “particular consequences for the making of social identities.” One of those was that people had to turn to official documents to compensate for a lack of direct, personal acquaintance. On the other hand, as Inspector Craddock reflects, they contribute to those changes: “partly because of” the rise of identity cards, which are so easily forged, “the subtler links that had held together English social rural life had fallen apart.”

It should be noted that those “subtler links” had a dark side that Miss Marple doesn’t acknowledge: they provided means by which elite members of society could police their boundaries, to make sure that no stranger — no one with the wrong “blood” or the wrong background — could falsely claim a place within the charmed circle. The Miss Marples of the world need to know not just “who it was that Lady Somebody’s daughter married” but also who is properly eligible to marry Lady Somebody’s daughter. Only if we know who people really are can we know whom to shun.

What makes Miss Marple distinctively insightful, and useful to the police, is her ability to transfer her minute observations of “the subtler links” that once held society together to a context in which those links have broken. The same small traits of speech and action that once would have instructed her in social belonging now enable her to discern social displacement. The same attentiveness that enabled her to interpret a social photograph now enables her to interpret its negative. The police can consult their records, can obtain files from their counterparts in Switzerland, but as servants of an administrative and bureaucratic regime they have no training in or understanding of the social cues Miss Marple has mastered.

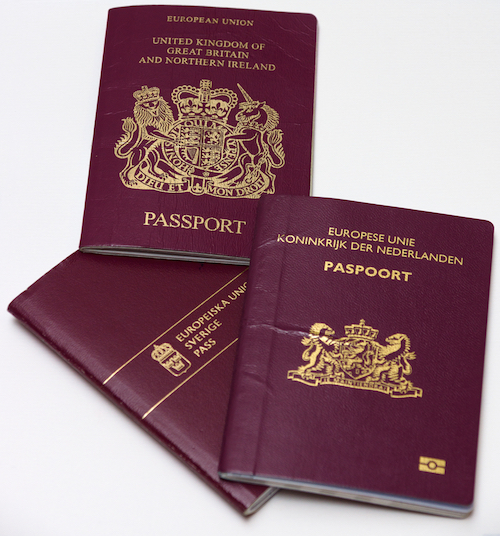

But, one might argue, Miss Marple’s local knowledge and sensitivity to social subtleties are required only because the reigning technologies of identity are so primitive. When Inspector Craddock laments the weak evidence provided by “nice neat identity cards with numbers on them, without photographs or fingerprints,” he is implicitly longing for better tech. Well, now we have it. Leo Benedictus notes that “The [current] Nicaraguan passport, for instance, boasts 89 separate security features, including ‘bidimensional barcodes,’ holograms and watermarks, and is reputed to be one of the least forgeable documents in the world.” For about a decade, the United States has been issuing passports with RFID chips capable of storing digital information; these chips have the capability (as yet unused) to store biometric information like fingerprint and eye scans. Other countries have already implemented biometric passports; for instance, all Swiss passports issued since 2010 have carried a chip with images of two of the bearer’s fingerprints. And the Unique Identification Authority of India is overseeing the largest project of this kind yet known, attempting — pending approval from the nation’s supreme court and parliament, which is not assured — to collect demographic and biometric data for every person in India and then assign to each person a twelve-digit identity number.

The little symbol in the bottom right of the frontmost passport in this picture indicates the presence of a chip capable of storing personal information, including fingerprints and eye scans. Copyright Sergey Kohl, via Shutterstock

The little symbol in the bottom right of the frontmost passport in this picture indicates the presence of a chip capable of storing personal information, including fingerprints and eye scans. Copyright Sergey Kohl, via Shutterstock

Amidst all these governmental projects, the forging of identities continues apace, regularly matching the improvements in official documents. In 2014, the artist Curtis Wallen wrote an article for The Atlantic describing how he created a wholly fictitious person named Aaron Brown, equipping Aaron with all the necessary identity documents and even with social media accounts. For Wallen, this was in part an art project and in part an exploration of the possibility of achieving true privacy in an online world, but it is also indicative of what some call the fungibility of identity in an online world — which is to say, a world in which our identities are always mediated by digital technologies, technologies that can be used for any imaginable purpose.

But if these technologies are so powerful, and cannot be reserved by the world’s governments for their own use, then we are back to Miss Marple’s problem: how to “find out if people are who they say they are.” In this light, it’s worth noting that a country with a particularly strict need to discern the identities and intentions of visitors, Israel, relies less on identity-document technology than on simple profiling — where are you coming from, what is the ethnicity of your name, what do you look like — and agents carefully trained to discern behavioral eccentricities. Getting through customs at Ben-Gurion Airport is like navigating a whole room full of Miss Marples.

This can be a slow and, if you’re singled out for further screening, excruciating process. But the discerning of strangers’ identities, when taken seriously, has always been slow: the passport rules established in the mid-nineteenth century were often neglected in the succeeding fifty years, likely because they were so tiresome to everyone concerned. However, with the increase in political tensions in the first years of the twentieth century — the same tensions that produced two world wars — passport rules began to be implemented more consistently in Western countries. But if anything has reliably increased in the past two hundred years, it is impatience with delays. For this reason, researchers, in Israel and elsewhere, have been trying to develop technological replacements for the kind of close observation that Miss Marple and the Israeli customs agents do: various forms of biometric analysis — Do your heartrate and respiration speed up when you’re asked pointed questions? — that will be, so researchers hope, more “objective” than the responses of human agents. Presumably Inspector Craddock would be pleased.

Even these Israeli customs officials, with all their Marpleian skills, are agents of the modern nation-state, which serves merely to reinforce a now-universal lesson: personal identity is both granted and confirmed by the state. The Catechism which the Church of England attached to its Book of Common Prayer starting in 1552 begins in this way:

Question. What is your name?

Aunswere. N. or M.

Question. Who gave you thys name?

Aunswere. My Godfathers and Godmothers in my baptisme, wherein I was made a member of Christe, the childe of god, and an inheritour of the kingdome of heaven.

According to this understanding, personal identity is summed up in one’s name, and one’s name is the joint gift of parents and church. The state has nothing to do with it. Therefore historians who want to know more about the demographics of any given (European) region in the distant past often rely on parish records — baptisms, weddings, funerals — since governmental records are typically scarce or nonexistent.

That has all changed. To see how completely, we need think only of current controversies over, say, transgendered people, whose struggle for legal recognition is based on the belief that while Bruce may think of himself as Caitlyn, Bruce cannot truly become Caitlyn until the state recognizes both the change in name and the change in sex. Caitlyn’s self-understanding could be clear and lasting: the person publicly known as Bruce may identify as (a telling phrase) a woman named Caitlyn; but the process of identity-formation is incomplete, truncated, until the state ratifies it. Social recognition may come easily and early: Wikipedia, for instance, may decide nearly instantly that the person who was Bruce is now Caitlyn. But only the ratification of the state is definitive. And in matters of identity, to ratify is almost to create: the decree of the state brings someone’s identity into being; that decree is what the speech-act theorists call a “performative utterance.”

For the Church of England in 1552, the power to make such an utterance was invested in family and church; for the British Foreign Office before 1858 — and for Miss Marple, in her informal and local way — it was invested in “some person of known respectability”; but for us the gift of identity is in the hands of the state. We learn, therefore, as James C. Scott might put it, to “see like a state”: to think of identity in the way the state does. Consider more closely, for instance, the act of naming. Scott points out that in pre-modern societies a person’s name might alter over time: “Among some peoples, it is not uncommon for individuals to have different names during different stages of life (infancy, childhood, adulthood) and in some cases after death…. A single individual will frequently be called by several different names, depending on the stage of life and the person questioning him or her.” The political regularization of names, and especially the creation of consistent surnames, is, Scott argues, essential to the stability and power of the modern nation-state. To give, establish, and ratify names is “to create a legible people.”

It is not easy to see — though I think it is necessary to see — how many of the technologies of modernity, from filing systems to postal systems, from photography to fingerprint analysis, have arisen in the service of making us “legible” to the state. We are all legible people now, and most of us see no alternative; thus the quests by so many to have their own sense of identity — who or what they “identify as” — be officially recognized by the state. If the state cannot read us — “legible” is from the Latin legere, “to read” — do we exist at all?

Further, the state’s distinctive ways of reading us are easily extended to private organizations, and especially commercial enterprises: consider how many financial transactions require the provision of one’s Social Security number as a means of establishing unique identity in ways that mere names cannot.* The larger the enterprise, the more its ways of seeing resemble those of governing bodies — and the closer it works with those bodies, though sometimes not close enough to suit governmental agencies, who demand “back doors” into customer data gathered by private companies. Thus Facebook, the largest social media company in the world, today demands that its users employ their “authentic identity,” as confirmed by a government-issued ID or by forms of nongovernmental ID that are themselves usually only obtainable with a government-issued ID. Facebook is trying to link its users’ identities as closely as possible with the ratification provided by the state.

Even Miss Marple puts her exceptional acuity in the service of this state-sponsored model of identity: she offers her local, personal, intuitive knowledge to supplement the deficiencies of police work, to fill in the gaps in official documentation, to bring people’s self-proclamations into line with governmental records. To “find out if people are who they say they are” is to set self-description against what the state sees, what the state reads.

This is what happens when the social structures — family, community, church — that were once key to the establishment of identity fade into insignificance, supplanted by the power of the modern nation-state. Miss Marple may seem to speak on behalf of those older, humbler sources of meaning, but in fact she quite coldbloodedly acknowledges their disappearance. “But it’s not like that any more…. And people just come — and all you know about them is what they say of themselves.” The task of the amateur detective is to bring “what they say of themselves” into line with what the state says of them; that is all. Because there is no alternative.

Thus the significance of the setting of A Murder Is Announced: not in Miss Marple’s native village of St. Mary Mead, but in a place where she knows only one family, a family almost wholly disconnected from the mystery that must be solved. In her first appearance in the book, she comments to some policemen, “Really, I have no gifts — no gifts at all — except perhaps a certain knowledge of human nature.” Not local knowledge, not intimate acquaintance with a specific community in all its particularity, but knowledge of “human nature.” And human nature is a very abstract and generalized thing to know. I can’t help being reminded of the titular character of Auden’s short poem “Epitaph on a Tyrant”: “He knew human folly like the back of his hand, / And was greatly interested in armies and fleets.” Miss Marple in her own way sees exactly like a state — and for the state.

Thus we conclude one chapter — the most recent to date — of a story that begins in the early modern period with the transfer of large numbers of people from Europe’s countryside to its cities. Social mobility is preceded by literal mobility: people who can walk or ride from one place to another. Economic and technological changes (starting with the building of roads) enabled that movement, then accelerated in order to accommodate it; this in turn has made further such movement more attractive, more inevitable. Supplemental technologies of writing, record-keeping, and administrative organization (including regular naming practices and travel documentation) have also arisen in order to keep track of all the movement and to prevent descent into social chaos. The result is the world we live in, a world in which we all must ask — in a tone and for a purpose quite alien to those of the person who coined this phrase — “Who is my neighbor?”

During Covid, The New Atlantis has offered an independent alternative. In this unsettled moment, we need your help to continue.